Abstract: Pellagra is a systemic disease resulting from a deficiency of niacin (vitamin B3) or its precursor tryptophan. Although largely eradicated in industrialized nations due to food fortification, it remains a significant issue in low-resource settings, among individuals with chronic alcoholism, malabsorptive disorders, or those on medications interfering with niacin metabolism. This article presents a comprehensive case of classical pellagra in a chronic alcoholic male, highlighting the importance of recognizing this preventable and treatable condition in modern clinical practice.

Introduction

Pellagra was first described in the 18th century and was historically endemic in populations reliant on maize as a staple food. The disease is classically characterized by the “three Ds”: dermatitis, diarrhea, and dementia. If left untreated, death—sometimes termed the “fourth D”—can occur.

Niacin is essential for the synthesis of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) and NAD phosphate (NADP), which are critical cofactors in redox reactions in metabolism. Deficiency can occur due to insufficient dietary intake, chronic alcoholism, malabsorption, carcinoid syndrome, or prolonged use of certain medications (e.g., isoniazid, hydantoin, azathioprine).

Despite being rare in developed countries, clinicians must maintain a high index of suspicion in susceptible individuals to prevent delayed diagnosis and mortality.

Case Report

Patient Profile

- Age/Sex: 52-year-old male

- Occupation: Unemployed

- Residence: Rural, low-income area

- Marital Status: Single, lives alone

Presenting Complaints

- Persistent watery diarrhea for 3 weeks (6–8 episodes/day)

- Progressive confusion, memory lapses, and irritability

- Hyperpigmented, scaly rash over sun-exposed areas (forearms, neck, face)

- Anorexia and general weakness

Medical and Social History

- Chronic alcohol consumption (~300 mL of local spirits/day for 20 years)

- Diet largely based on maize flour (ugali), minimal animal protein

- No known chronic illnesses, no medications

Physical Examination

- General: Cachectic, dehydrated, disoriented

- Vital signs: BP 110/70 mmHg, HR 98 bpm, Temp 37.5°C

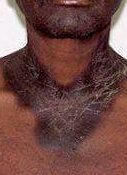

- Skin: Symmetrical hyperpigmented and scaly rash on dorsal hands, forearms, neck (Casal’s necklace), perioral region

- Neurological: Confused, with mild tremors; Mini-Mental State Exam score: 19/30

- GI: Mild abdominal tenderness, hyperactive bowel sounds

- Others: Mild pedal edema, glossitis, stomatitis

Investigations

- CBC: Hemoglobin 10.5 g/dL, MCV 104 fL (macrocytic anemia)

- Liver function tests: Elevated AST (76 U/L), ALT (54 U/L), GGT elevated

- Serum albumin: 2.8 g/dL (low)

- Electrolytes: Mild hyponatremia

- Vitamin B3 (niacin) level: Low

- Stool analysis: No parasites or leukocytes

- Serum B12 and folate: Normal

- HIV, hepatitis B/C serologies: Negative

Diagnosis

Classical pellagra secondary to chronic alcoholism and dietary deficiency

Treatment

- Nicotinamide: 300 mg/day PO in divided doses (initially), then tapered

- Multivitamin supplementation: Daily

- High-protein diet with niacin-rich foods (meat, legumes, dairy)

- IV fluids for rehydration

- Psychosocial support: Referral to addiction rehabilitation

Outcome

By day 5, improvement was noted in mental status and resolution of diarrhea. Skin lesions began to regress by the second week. The patient was discharged after 14 days and followed up for nutritional counseling and alcohol cessation support.

Discussion

Pellagra is a rare but significant nutritional disorder in modern practice. It results either from inadequate intake of niacin or impaired conversion of tryptophan to niacin. Chronic alcoholism, as seen in this case, interferes with absorption, metabolism, and dietary intake, creating a multifactorial risk.

Pathophysiology

Niacin (vitamin B3) is a precursor for NAD and NADP. Deficiency leads to impaired energy metabolism, particularly affecting the skin, gastrointestinal tract, and central nervous system. Tryptophan, an essential amino acid, can be converted to niacin—thus, diets low in tryptophan or interference with this pathway (e.g., carcinoid syndrome, Hartnup disease) may also precipitate pellagra.

Clinical Manifestations

- Dermatitis: Photosensitive rash, usually bilaterally symmetrical, resembling sunburn initially, followed by hyperpigmentation and scaling.

- Diarrhea: Atrophic changes in intestinal mucosa lead to malabsorption.

- Dementia: Neuropsychiatric symptoms range from irritability and depression to encephalopathy and psychosis.

Differential Diagnoses

- Zinc deficiency

- Vitamin B12 deficiency (subacute combined degeneration)

- Dermatomyositis

- Lupus erythematosus

Diagnostic Approach

Clinical diagnosis is often sufficient in endemic areas or with suggestive history. Niacin levels or NAD/NADP ratios may be helpful in uncertain cases, although not always readily available.

Treatment and Prognosis

Nicotinamide is preferred over niacin for its better side-effect profile. Rapid clinical improvement is typically seen within days of treatment. Long-term management includes addressing underlying causes and ensuring adequate nutritional intake.

Public Health Perspective

Pellagra has nearly vanished in developed nations due to niacin fortification of cereals. However, it remains endemic in parts of sub-Saharan Africa, Southeast Asia, and among marginalized populations in developed countries. It serves as a reminder of the intersection between poverty, nutrition, and health.

Conclusion

This case illustrates the classical presentation of pellagra in a vulnerable patient. It emphasizes the importance of nutritional assessment in clinical evaluation, especially in individuals with substance use disorders. Timely recognition and treatment of pellagra result in full recovery and prevent fatal outcomes.

References

- World Health Organization. Pellagra and Niacin Deficiency. WHO Reports, 2020.

- Lanska DJ. Pellagra and the Origin of Vitamin Therapy. Ann Neurol. 2002;52(1):107-109.

- Hegyi J, Schwartz RA, Hegyi V. Pellagra: Dermatitis, Dementia, and Diarrhea. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43(1):1-5.

- Fagerberg SE. Pellagra in Alcoholics. Am J Clin Nutr. 1974;27(7):807-812.

- Rao DR et al. Pellagra and Its Prevention. Indian J Med Res. 2017;146(Suppl):S19–S25.