Abstract

Mpox (formerly known as monkeypox) is a viral zoonotic disease caused by the monkeypox virus (MPXV), an orthopoxvirus related to smallpox. First identified in 1958 and seen in humans in 1970, mpox remained endemic in Central and West Africa for decades. However, the global outbreak in 2022 highlighted its potential for rapid human-to-human transmission beyond endemic regions. This article explores the virology, epidemiology, clinical features, diagnosis, treatment, prevention strategies, and the implications of mpox as a global public health threat.

Introduction

Mpox is an emerging zoonosis caused by the monkeypox virus (MPXV), a double-stranded DNA virus belonging to the genus Orthopoxvirus in the family Poxviridae. Historically confined to forested areas of Central and West Africa, the virus has gained global attention following outbreaks in non-endemic countries. The 2022 outbreak, particularly, demonstrated community spread in urban populations, often among men who have sex with men (MSM), raising concerns of sustained human-to-human transmission.

Virology and Pathogenesis

MPXV is closely related to the variola virus (which causes smallpox), vaccinia virus (used in the smallpox vaccine), and cowpox virus. There are two distinct genetic clades:

- Clade I (Central African/Congo Basin clade): More virulent with a higher case fatality rate (up to 10%).

- Clade II (West African clade): Less severe, with a fatality rate below 1%.

Transmission occurs through:

- Zoonotic transmission: Direct contact with blood, bodily fluids, or cutaneous/mucosal lesions of infected animals (e.g., rodents, primates).

- Human-to-human transmission: Respiratory droplets, direct contact with skin lesions, contaminated materials (fomites), and, as recently highlighted, intimate sexual contact.

The virus invades via broken skin, respiratory tract, or mucous membranes, replicates in local lymph nodes, then disseminates hematogenously causing systemic symptoms.

Epidemiology

Historical Context

- First identified in 1958 in monkeys used for research.

- First human case in 1970 in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

- Endemic outbreaks in Central and West Africa, with occasional imported cases in non-endemic countries.

Global Outbreak of 2022

In May 2022, the World Health Organization (WHO) reported multi-country outbreaks in non-endemic regions. Over 80,000 cases were reported across more than 100 countries by the end of 2022.

Key epidemiological shifts included:

- Predominant involvement of MSM populations.

- Transmission through sexual networks.

- Widespread community transmission outside endemic areas.

In July 2022, WHO declared mpox a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC).

Clinical Features

Incubation Period

- Typically 6–13 days (range: 5–21 days).

Prodromal Phase

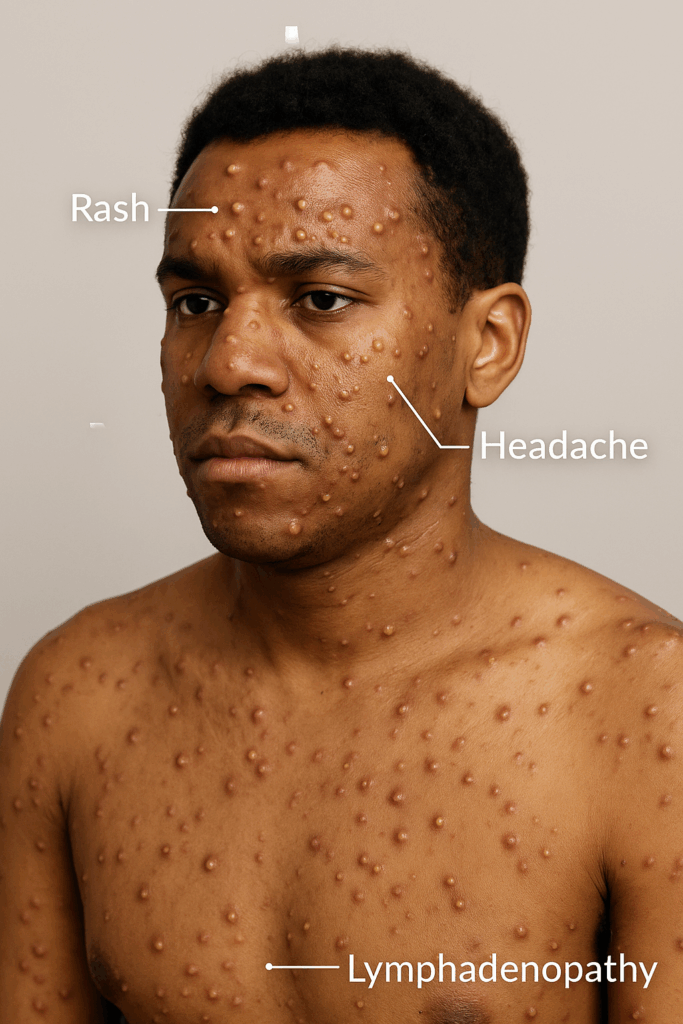

- Fever

- Headache

- Myalgia

- Back pain

- Fatigue

- Lymphadenopathy (distinguishing feature from smallpox)

Rash Phase

- Begins 1–3 days after fever onset.

- Lesions progress through stages:

- Macules

- Papules

- Vesicles

- Pustules

- Scabs

- Lesions are often synchronous and centrifugally distributed.

- Atypical presentations (localized rash, genital lesions) were common in the 2022 outbreak, particularly among sexually active individuals.

Complications

- Secondary bacterial infections

- Bronchopneumonia

- Sepsis

- Encephalitis

- Ocular infections leading to loss of vision

Case fatality rates vary by clade and population (1–10%).

Diagnosis

Laboratory Testing

- Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR): Gold standard for diagnosis; performed on lesion samples (e.g., swabs of vesicles, pustules, or scabs).

- Serology: Can detect anti-orthopoxvirus IgM/IgG, though cross-reactivity with other poxviruses limits specificity.

- Viral culture: Less commonly used due to biosafety requirements.

Differential Diagnoses

- Varicella (chickenpox)

- Herpes simplex

- Syphilis

- Molluscum contagiosum

- Other vesiculopustular rashes

Treatment

Mpox is usually self-limiting, and most cases resolve within 2–4 weeks.

Supportive Care

- Hydration

- Pain management

- Treatment of secondary infections

Antiviral Therapies

- Tecovirimat (TPOXX): Approved under expanded access; inhibits viral envelope formation.

- Brincidofovir and Cidofovir: Broad-spectrum antivirals with potential efficacy but more adverse effects.

These are reserved for severe cases or at-risk populations (e.g., immunocompromised patients, pregnant women, children).

Prevention and Vaccination

Smallpox Vaccination

Historically, smallpox vaccination provided cross-protection (~85%) against mpox. However, routine vaccination ceased after smallpox eradication in 1980, leading to an increase in susceptible populations.

Newer Vaccines

- MVA-BN (Modified Vaccinia Ankara – Bavarian Nordic): A non-replicating live vaccine approved for prevention of smallpox and mpox.

- ACAM2000: A replicating smallpox vaccine; more side effects; not recommended for immunocompromised individuals.

Infection Control

- Isolation of infected individuals

- PPE for healthcare workers

- Disinfection of contaminated surfaces

- Sexual health education in high-risk populations

Public Health Implications

The 2022 mpox outbreak underscored the vulnerability of global health systems to emerging zoonoses, particularly in the context of globalization, travel, and changing social behaviors.

Key Lessons

- Need for robust surveillance and rapid diagnostic capacity.

- Importance of non-stigmatizing public health messaging, especially in at-risk communities.

- Global collaboration for equitable access to vaccines and antivirals.

- Greater investment in zoonotic spillover prevention and One Health approaches.

Conclusion

Mpox has transitioned from a rare zoonosis to a significant global health concern. While the virus is less transmissible and less deadly than smallpox, its ability to spread through close contact and produce outbreaks in non-endemic settings is alarming. Vigilance, public health preparedness, research into vaccines and therapeutics, and international cooperation are essential to curb its spread and prevent future outbreaks.

References

- World Health Organization. Mpox (Monkeypox). https://www.who.int/

- CDC. Monkeypox Information for Healthcare Professionals. https://www.cdc.gov/

- Adler H, Gould S, Hine P, et al. Clinical features and management of human monkeypox: a retrospective observational study in the UK. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022.

- Bunge EM, et al. The changing epidemiology of human monkeypox—A potential threat? A systematic review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2022.